“LAMPEDUSA 2050” FICTIONAL ARTICLE

PUBLISHED ON DESIRED LANDSCAPES #2 · WRITTEN BY VINCENZO ANGILERI · VISUALS BY MATT KENNEDY AND ADRIÀ CAÑAMERAS · 2020

Written by VINCENZO ANGILERI

Visualizations by MATT KENNEDY

Photography by ADRIÀ CAÑAMERAS

Published on DESIDERED LANDSCAPES Nº3

Athens, Greece (2020)

“LAMPEDUSA 2050” FICTIONAL ARTICLE

PUBLISHED ON DESIRED LANDSCAPES #2 · WRITTEN BY VINCENZO ANGILERI · VISUALS BY MATT KENNEDY AND ADRIÀ CAÑAMERAS · 2020

'THE ISLAND BETWEEN TWO WORLDS' LAMPEDUSA 2050

Our ferry left a few hours ago from Porto Empedocle, a town of writers and mathematicians on the southernmost coast of Sicily. We are heading to Lampedusa, an island in the middle of the Mediterranean and the most symbolic gateway between Africa and Europe. The ferry is crowded. A group of students from the University of Palermo is discussing what they’ll have for dinner. Behind them, a few early tourists have come to catch the shy beginnings of summer. A noisy child has been running past my seat for hours, while her mother reads nervously on an old Kindle.

And now, there it is: Lampedusa, the not-quite eight square miles of Italian territory in the Mediterranean. Once known globally not as a celebration of coexistence but for tragedy. For decades, its sparkling waters and postcard-perfect beaches served as a jarring backdrop for migrant boat landings. The island is closer to Africa than to Europe—about 70 miles from the Tunisian coast and further south than Malta. Until one summer, 30 years ago, in July 2020, when everything changed.

SUMMERS OF PASSION

Yes, summer. Here, the arrival of the season used to carry a different meaning. June marked the beginning of migrant boats attempting to reach these shores. And sometimes, often, they failed.

It was the summer of 2018 when I first visited Lampedusa. I was covering yet another shipwreck. It was a day much like this: the breeze was soft, the air warm, the sea eerily calm. That day, at least 13 women—some pregnant—drowned when their overcrowded boat capsized moments before rescue. It wasn’t an exception. In the previous two decades, 400,000 migrants had already arrived via the Mediterranean, with many more losing their lives at sea.

By 2015, the global refugee crisis was in full force. With a population of only 6,000 and an economy reliant on fishing and tourism, Lampedusa descended into chaos. Refugees from Syria, Libya, Eritrea, the Gambia, Sudan, Tunisia, and beyond arrived on its shores as nationalism surged across Europe. Far-right parties began to thrive, fueled by a narrative of closed borders and scaremongering. What we now know was a twilight—the crisis of the nation-state as a political form—was then perceived as an emergency, a war. Between 2015 and 2020, an estimated 6,700 people were swallowed by the sea.

But one day, this all ended. At 2 a.m. on July 9, 2020, the last overcrowded fishing boat drifted less than half a mile off Lampedusa. The 420 people packed onboard would be the island’s last undocumented arrivals. A week later, a delegation of politicians from the EU and AU—joined by representatives of the Middle East Peace League and local citizens—declared Lampedusa a “Free City” under the Sea Peace Act. The world watched as history was made.

THE SQUARE OF THE RISEN SEA

Looking at today’s Lampedusa, it’s hard to imagine such a past. The Lampedusa of 2050 is a splendid, thriving city—a modern symbol of the Mediterranean’s golden age, where diverse cultures coexisted in the absence of nation-states. Reclaiming its place in history, the island now represents unity in a fragmented world.

As our ferry slows, the noisy child has fallen asleep in her father’s arms. The students rush to disembark, and tourists pepper local officers with questions. On the dock, taxis and cars jostle for position. A driver beckons, “Taxi, taxi! Vuole taxi, signore? La porto al suo hotel? Amuní, acchianasse!” Magnetized, I agree, and he whisks me to La Luce, one of the city’s most iconic landmarks.

The countryside, dry and scrubby like Tunisia yet as mysterious as Italy, gives way to the lights of the city. The driver, detecting my foreign accent, asks about my last visit. “Almost 30 years ago,” I reply.

“Maró! It was a different island back then! Everything has changed. My daughters are still here—the eldest just started at the university. If someone had told me this decades ago, I wouldn’t have believed it.”

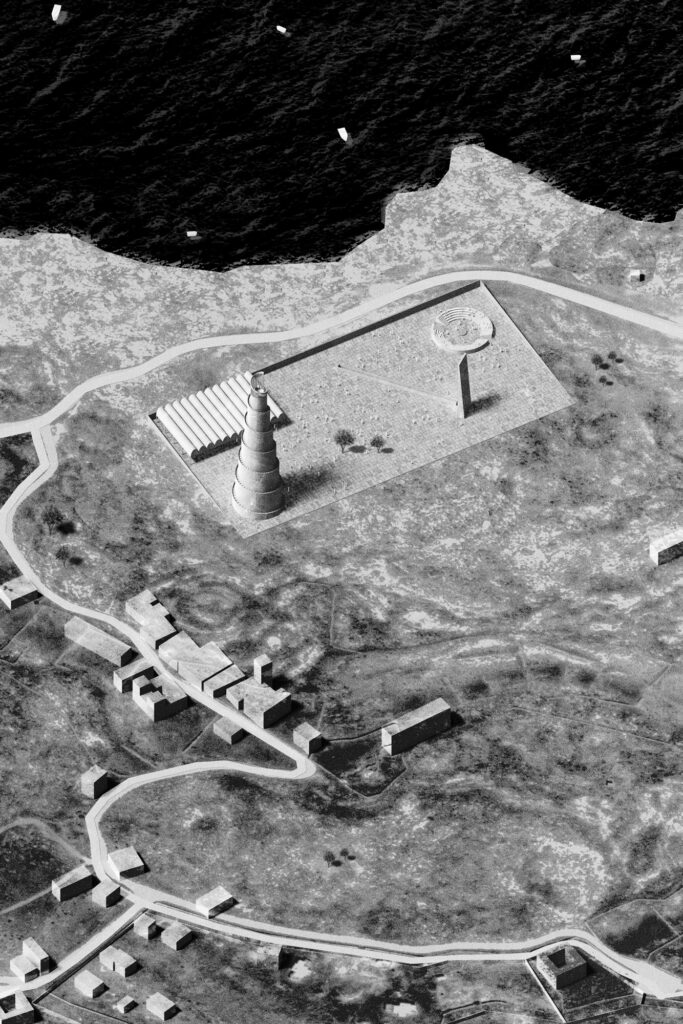

He’s referring to the University of the Mediterranean, founded over a decade ago in partnership with European, African, and Middle Eastern institutions. Located within the grand Migrants’ Arrival complex, built in 2023, the university is now a hub for cultural and academic exchange.

Giovanni hands me his card, along with a few from local restaurateurs who share his surname. “La famiglia prima di tutto,” he says before leaving me at La Luce.

TO EXIST IS TO BE ON THE MAP

Not long ago, maps of Italy ended at Sicily, and maps of Africa ignored Lampedusa. Now, Lampedusa isn’t just on the map—it has put the Mediterranean back in focus. The sea, once the cradle of ancient civilization and later a graveyard, now shines as a beacon of hope and unity. From Lebanon to Gibraltar, Libya to Sicily, modern Lampedusa stands as a testament to what can be achieved when borders dissolve, and coexistence triumphs. You don’t need to visit to understand its significance, you just need to know it exists.

***